Translation

Recordings

A Good Washing

Passing (Things) On

Closing

Back To Top

Abstract

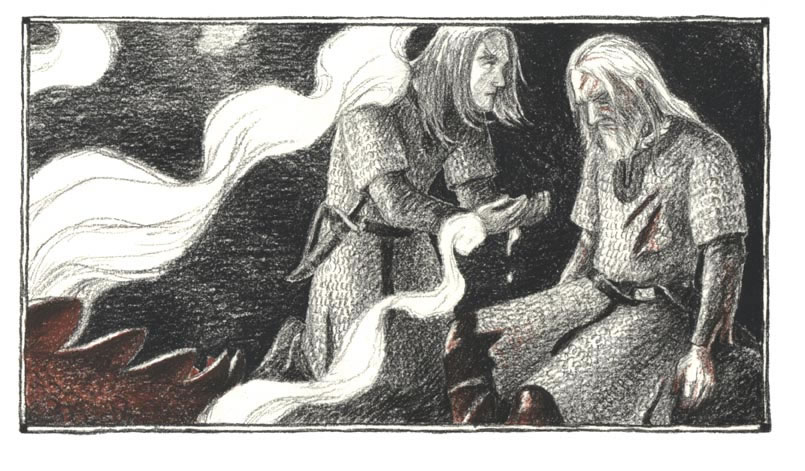

Wiglaf tends to Beowulf and Beowulf begins to speak to Wiglaf, signalling that his death is imminent.

Back To Top

Translation

"Then he with hand, blood-stained,

the famed lord, a man unmatched for good,

washed his dear lord with water,

battle-worn, and unclasped his helm.

Beowulf spoke - he spoke through the pain,

the ache, of his miserably vexatious wound; well he knew,

that he had fulfilled the days of his life,

of earthen joy; that all of his life-time had

fled, death was immeasurably near:

'Now I to the son of mine would give

the war garments, if it had been so granted

by fate that I any heir had,

flesh of my flesh.'"

(Beowulf ll.2720-32a)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

{Forthcoming}

Modern English:

{Forthcoming}

Back To Top

A Good Washing

The washing of Beowulf requires some note here.

First, there's the general importance of the act as a means of humbling yourself before someone whom you respect.

Then there's the fact that it's a simple act of subservience, the sort of thing that is an active display of obedience and respect.

And that interpretation of the act leads into the Christian significance. However, if this death is meant to mirror that of Christ in the New Testament, then there's something interesting going on here.

In the NT and in the Catholic ritual recreating the Last Supper, it's Christ who washes his disciples' feet.

Wiglaf's washing is more general, but if the parallels between these stories are followed, then Wiglaf is effectively becoming the Christ figure of the story, possibly in a more meaningful way than Beowulf.

Yes, Beowulf defeated the dragon, but that cost him his life, and Beowulf would never be characteristically elegiac if he came back to life afterwards (nor would the Anglo-Saxons have told it like that, regardless of whatever their source material may have been).

This transference of Christ-ness might even have been one of the original purposes of the poem as a conversion tool, since it's the sort of succession that Anglo-Saxon's would have understood. After all, it's the exact same way that kingship would be transferred when no heir was available: through a ritualistic act and acknowledgement.

Back To Top

Passing (Things) On

The opening of Beowulf's speech also says a lot about the Christian intent of the written version of the poem.

If Beowulf is taken as a heroic heathen, someone who is Christian in all ways but name (ignore for a moment, his constant references to a single 'Lord of Men'/'Ruler'/'King of Glory'), then he simply can't have an heir. There can be no continuation of the virtuous heathens, since there is no further need for such people, the virtuous will, of course, be Christians. And so enter the transitional figure of Wiglaf, the one who reprimands the cowardly thanes and does his best to guide Geatland gently into the good night awaiting it after Beowulf's death.

Beowulf signals his death not by saying that he has reached the end, as the poet/scribe does before we get his dialogue, but by saying that he has no heir to give his weapons to.

He has no offspring that he could call "flesh of my flesh" (or "belonging to my body" for a curiously medieval Christian rendering of "lice gelenge" (l.2732)) that can continue his line directly. And so, it passes to one who's proven himself to be worthy: Wiglaf.

However, it's important that Beowulf opens his speech with talk of handing down his war garb. Because Wiglaf is not his son, the war garb will not be touching the same flesh (more practically, it may also be less of a snug fit than on any son of Beowulf). As a result, Wiglaf is not going to be able to do the same things that Beowulf did with his gear, in both the literal and figurative senses.

And that a body patently different from Beowulf's carries forward the symbols of the old way embodied by Beowulf's war garb (arguably, his most precious possession) is a great metaphor for the spread of Christianity throughout Early Medieval Europe.

Back To Top

Closing

Check back here next week, for Isidore's finishing off the first section of book 12 with further discussion of fertility lore, and for Beowulf's quick review of his kingship and current predicament.

Back To Top

No comments:

Post a Comment