Abstract

Translation

Recordings

The Dead Become Dragons?

Dealing with Dragons

Closing

Back To Top

Abstract

Wiglaf and several other Geats raid the hoard, and then bring Beowulf and their haul to Hronesness for the hero's funeral.

Back To Top

Translation

Indeed the wise son of Weohstan

summoned a band of the king's thanes,

seven together, those who were best,

he went with seven others, warriors,

under the evil roof; one bore in hand

a flaming torch, the one who went at the front.

There was no drawing of lots for the plundering of

that hoard, when the men saw that all parts of

the hall remained without a guardian,

for he lay wasting away; few of them grieved

as they hastily carried out those

dear treasures; the dragon also was pushed,

the serpent they slid over the sea cliff, let the waves

take him, the sea enfolded that guardian of precious

things. Then was wound gold loaded onto wagons,

everything in countless numbers, then was the prince borne,

the old warrior brought to Hronesness.

(Beowulf ll.3120-3136)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

{Forthcoming}

Modern English:

{Forthcoming}

Back To Top

The Dead Become Dragons?

There's something to be said for efficiency. And, here efficiency could be something pointing towards a parallel that's merely been suggested beforehand.

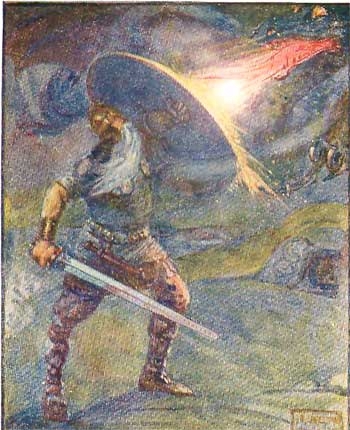

As far as the poem describes it, the Geats move Beowulf over to Hronesness in the same load, or at least trip, as the gold that they've taken from the hoard. Beowulf is certainly worthy to ride with such treasures, but laying him on this heap of heirlooms is really quite strange, especially if you consider what happens to the dragon.

It's a small act, but there's so much going on in it. The projection of value onto wealth, the equation of treasured objects with treasured people, perhaps even a glimpse into a philosophy of the soul. For, the Anglo-Saxons might have regarded the body as merely a vessel, much like the cups found in the hoard, something that can be shining and gold adorned, but that maybe has its greatest value when it is filled with mead, just as a body might have its greatest value while it still holds a soul.

Among the strangest of the things that it suggests (and this is something suggested by the act of burying people of high esteem with objects of high esteem), is that in death great people are made into what, if living, could be considered a dragon. They're in a barrow, surrounded by gold, and, in the case of Beowulf, there is always flame nearby. Even in the case of people like Scyld Scefing, who were pushed off to sea in ships ladened with treasure and then put to flame, all of the key aspects of a dragon can be found.

Back To Top

Dealing with Dragons

Yet, what do the Geats do with a proper dragon? They just dump it over the cliff and let it fall into the water. Keeping the written Beowulf's Christian influences in mind, I wonder if doing so is as bad as dying in a fire is to the Greeks. In either case your body isn't being properly preserved, which, strictly theologically speaking, means you will not be able to be judged come the second coming.

Moreover, though, it's also a denial of the cyclical nature of life as laid down throughout the Bible: 'people are dust and unto dust they will return.' Perhaps, in a way, destroying a body but not burying it was intended as a way to keep another manifestation of that thing from appearing. If such is the case, then the ceremonial funerals of great figures from this period and earlier could be explained as a means of propagating greatness, or re-introducing it into the life-cycle.

But then, for a people like the Geats, who face difficulty on all sides and even among themselves believe they'll be wiped out, what does such a funeral mean? Is it merely to be a monument to the greatest of a long forgotten people? Is it, in the case of Beowulf, just a convenient excuse to build a lighthouse?

Back To Top

Closing

Next week, Beowulf burns.

Back To Top

A place where dead languages live again - revived by an admirer of words. Currently, (loose) Latin and (spot-on) Old English.

Showing posts with label dragon. Show all posts

Showing posts with label dragon. Show all posts

Thursday, April 25, 2013

Dragons and Death (ll.3120-3136) [Old English]

Labels:

Anglo-Saxon,

Beowulf,

death,

dragon,

poetry,

translation

Thursday, February 28, 2013

Wondering about the Strange and the Draconic (ll. 3033-3046) [Old English]

Abstract

Translation

Recordings

Dragon Gawking

Of Dragonkind

Closing

Back To Top

Abstract

The Geats come down to where Beowulf died, but are distracted by a more wondrous sight.

Back To Top

Translation

They found him on the sand where his soul left his body

emptily guarding his couch, he who had given rings

in days past; that was the final day

of that good man's journey, indeed that great-king,

lord of the Weders, died a wondrous death.

Yet before that they saw a stranger creature,

opposite him there on the strand was the serpent, there

the loathed one lay: it was the dweller of the drake's

den,the sombrely splattered horror, glowing like an

ember for its flames. It was full fifty feet long,

laying there; just days ago it knew

the joy of night-flight, keeping a searching eye out for

its den down below; it was held there in death,

never again would it know its earth den.

(Beowulf ll.3033-3046)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

{Forthcoming}

Modern English:

{Forthcoming}

Back To Top

Dragon Gawking

The first thing to ask after reading this passage is: Why does the dragon get so much attention?

It's the "loathed" enemy ("laa[th]ne" l.3040), and Beowulf overcame it. So why spend nine lines going into detail about it?

There are a few possibilities here. The Anglo-Saxon audiences of the poem before it was written down probably had a good sense of a creature's strength. More than likely, simply by hearing about him, her, or it, even. The prevalance and power of boasting among them definitely attests to such an idea. But any culture that can so readily size up opponents needs some sort of metric to go by. So, maybe, all of this extra detail about the dragon is provided to show how Beowulf is at least equal to the dragon, since they mutually slew one another.

Or, maybe the point of having such detail isn't to compare it to Beowulf in terms of strength at all. Instead, maybe it's more about their common strangeness. For, whatever a man's boasts were in those days, few would have crossed paths with monsters as varied and powerful as those that Bwowulf scuffled with. In that sense, then, maybe this passage is suggesting that Beowulf himself should be viewed as a kind of monster. Or, at the very least, a wonder.

Maybe this is why Beowulf was bound together with a life of Saint Christopher, Wonders of the East, and a Letter of Alexander to Aristotle. Rather than being about a normal person going around the world and finding oddities, Beowulf offered audiences a glimpse into the perspective of a creature as rare and wonderful as dog-headed men, or a land over which thick darkness has settled.

Back To Top

Of Dragonkind

Matters of the dragon and Beowulf sharing the page in this excerpt aside, there's the question of what kind of dragon it is. Given its description here, it sounds more like an Oriental dragon than an Occidental one. It must be rather thin (its fire burning through its skin can be seen long after it's dead), it can fly but no real mention of wings is made in the poem, and, at least so far as I'm imagining it, it seems like it's coiled up in death.

Why should the kind of dragon that Beowulf and Wiglaf defeated matter?

Well, one of the biggest influences on Beowulf (particularly its being written down) was Christianity. Of course, Christianity isn't without its depictions of dragons. These, though, especially up to the early Medieval period, are generally of a serpentine beast that's supposed to be the devil incarnate. Maybe there's a bit of that here too, but it seems more likely that having a unique dragon is just another reason that the book was bound with fantastic tales from around the known world.

Back To Top

Closing

Next week, the poem moves from treasure-hoarder to treasure itself. Don't miss it!

Back To Top

Translation

Recordings

Dragon Gawking

Of Dragonkind

Closing

Back To Top

Abstract

The Geats come down to where Beowulf died, but are distracted by a more wondrous sight.

Back To Top

Translation

They found him on the sand where his soul left his body

emptily guarding his couch, he who had given rings

in days past; that was the final day

of that good man's journey, indeed that great-king,

lord of the Weders, died a wondrous death.

Yet before that they saw a stranger creature,

opposite him there on the strand was the serpent, there

the loathed one lay: it was the dweller of the drake's

den,the sombrely splattered horror, glowing like an

ember for its flames. It was full fifty feet long,

laying there; just days ago it knew

the joy of night-flight, keeping a searching eye out for

its den down below; it was held there in death,

never again would it know its earth den.

(Beowulf ll.3033-3046)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

{Forthcoming}

Modern English:

{Forthcoming}

Back To Top

Dragon Gawking

The first thing to ask after reading this passage is: Why does the dragon get so much attention?

It's the "loathed" enemy ("laa[th]ne" l.3040), and Beowulf overcame it. So why spend nine lines going into detail about it?

There are a few possibilities here. The Anglo-Saxon audiences of the poem before it was written down probably had a good sense of a creature's strength. More than likely, simply by hearing about him, her, or it, even. The prevalance and power of boasting among them definitely attests to such an idea. But any culture that can so readily size up opponents needs some sort of metric to go by. So, maybe, all of this extra detail about the dragon is provided to show how Beowulf is at least equal to the dragon, since they mutually slew one another.

Or, maybe the point of having such detail isn't to compare it to Beowulf in terms of strength at all. Instead, maybe it's more about their common strangeness. For, whatever a man's boasts were in those days, few would have crossed paths with monsters as varied and powerful as those that Bwowulf scuffled with. In that sense, then, maybe this passage is suggesting that Beowulf himself should be viewed as a kind of monster. Or, at the very least, a wonder.

Maybe this is why Beowulf was bound together with a life of Saint Christopher, Wonders of the East, and a Letter of Alexander to Aristotle. Rather than being about a normal person going around the world and finding oddities, Beowulf offered audiences a glimpse into the perspective of a creature as rare and wonderful as dog-headed men, or a land over which thick darkness has settled.

Back To Top

Of Dragonkind

Matters of the dragon and Beowulf sharing the page in this excerpt aside, there's the question of what kind of dragon it is. Given its description here, it sounds more like an Oriental dragon than an Occidental one. It must be rather thin (its fire burning through its skin can be seen long after it's dead), it can fly but no real mention of wings is made in the poem, and, at least so far as I'm imagining it, it seems like it's coiled up in death.

Why should the kind of dragon that Beowulf and Wiglaf defeated matter?

Well, one of the biggest influences on Beowulf (particularly its being written down) was Christianity. Of course, Christianity isn't without its depictions of dragons. These, though, especially up to the early Medieval period, are generally of a serpentine beast that's supposed to be the devil incarnate. Maybe there's a bit of that here too, but it seems more likely that having a unique dragon is just another reason that the book was bound with fantastic tales from around the known world.

Back To Top

Closing

Next week, the poem moves from treasure-hoarder to treasure itself. Don't miss it!

Back To Top

Labels:

Beowulf,

death,

dragon,

Old English,

poetry,

translation,

Wiglaf

Thursday, December 6, 2012

Appraising a Dagger via a Sword

Abstract

Translation

Recordings

Reading Steel

Ouroboros Slinks in

Closing

Back To Top

Abstract

The messenger sent by Wiglaf tells the waiting people of Beowulf's fate, and Wiglaf's steadfastness.

Back To Top

Translation

"'Now is the Weder's gracious giver,

the lord of the Geats, fast in his deathbed,

gone to the grave by the dragon's deed:

Beside him, in like state, lay the

mortal enemy, dead from dagger wounds; for that sword

could not work any wound whatever on

that fierce foe. Wiglaf sits

by Beowulf's side, the son of Weohstan,

a warrior watching over the unliving other,

holding vigil over the Geats' chief,

he sits by the beloved and the reviled.'"

(Beowulf ll.2900-2910a)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

Modern English:

Back To Top

Reading Steel

The emphasis that the messenger puts on the dagger is strange. It's not that he goes out of his way to praise it, but the fact that he makes it clear that the sword was useless. This extra detail suggests that the sword was indeed considered the proper, noble weapon, while the dagger held a lower position on the symbolic/social scale of weapons. Nonetheless, the connotation of Beowulf's dagger use underlines just what the Geats lose when they lose Beowulf.

It was likely standard among Anglo-Saxons to carry a dagger of some kind with them, along with their swordbelt. However, even in the heat of the moment, the poet peels things back and tells us that Beowulf wore his dagger on his hip/byrnie.

So was the wearing of a smaller blade a new thing with Beowulf's generation? Was it simply the garb of a proper warrior? Why does the poet specify where Beowulf wore his dagger?

Such a small detail, though potentially of some historical or cultural significance, is more likely than not just an example of the poet filling out his poetic meter. The mention of the sword's failure, as an explanation for the use of the dagger definitely shows that the messenger is true to his word - he leaves out no detail.

And that honesty opens up the other side of the issue, it seems very likely that the sword is only mentioned to excuse the dagger. In fact, if you've read Beowulf enough times, you can almost see the crowd rolling their eyes and thinking that Beowulf's just being Beowulf, being too strong for any sword and whatnot.

Back To Top

Ouroboros Slinks in

Yet, if we turn the mention of the dagger again, then there's the matter of the dragon's existence in the story being cyclical. The dragon appears because a thief steals from its hoard.

A dagger is weapon of favour among those who prize stealth (like thieves) - hence the modern genre tag "cloak and dagger" - and so is likely to be a thief's weapon. The dragon is killed with a dagger, and so the dragon's existence in the story is something of a closed system. A noble sword is wielded, but in the end what woke the dragon must put it back to its rest.

Back To Top

Closing

Next week, watch for the prognostications of the messenger on Thursday! I'll also be uploading links to any British/Medieval archaelogical news that I come across.

Back To Top

Translation

Recordings

Reading Steel

Ouroboros Slinks in

Closing

Back To Top

Abstract

The messenger sent by Wiglaf tells the waiting people of Beowulf's fate, and Wiglaf's steadfastness.

Back To Top

Translation

"'Now is the Weder's gracious giver,

the lord of the Geats, fast in his deathbed,

gone to the grave by the dragon's deed:

Beside him, in like state, lay the

mortal enemy, dead from dagger wounds; for that sword

could not work any wound whatever on

that fierce foe. Wiglaf sits

by Beowulf's side, the son of Weohstan,

a warrior watching over the unliving other,

holding vigil over the Geats' chief,

he sits by the beloved and the reviled.'"

(Beowulf ll.2900-2910a)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

Modern English:

Back To Top

Reading Steel

The emphasis that the messenger puts on the dagger is strange. It's not that he goes out of his way to praise it, but the fact that he makes it clear that the sword was useless. This extra detail suggests that the sword was indeed considered the proper, noble weapon, while the dagger held a lower position on the symbolic/social scale of weapons. Nonetheless, the connotation of Beowulf's dagger use underlines just what the Geats lose when they lose Beowulf.

It was likely standard among Anglo-Saxons to carry a dagger of some kind with them, along with their swordbelt. However, even in the heat of the moment, the poet peels things back and tells us that Beowulf wore his dagger on his hip/byrnie.

So was the wearing of a smaller blade a new thing with Beowulf's generation? Was it simply the garb of a proper warrior? Why does the poet specify where Beowulf wore his dagger?

Such a small detail, though potentially of some historical or cultural significance, is more likely than not just an example of the poet filling out his poetic meter. The mention of the sword's failure, as an explanation for the use of the dagger definitely shows that the messenger is true to his word - he leaves out no detail.

And that honesty opens up the other side of the issue, it seems very likely that the sword is only mentioned to excuse the dagger. In fact, if you've read Beowulf enough times, you can almost see the crowd rolling their eyes and thinking that Beowulf's just being Beowulf, being too strong for any sword and whatnot.

Back To Top

Ouroboros Slinks in

Yet, if we turn the mention of the dagger again, then there's the matter of the dragon's existence in the story being cyclical. The dragon appears because a thief steals from its hoard.

A dagger is weapon of favour among those who prize stealth (like thieves) - hence the modern genre tag "cloak and dagger" - and so is likely to be a thief's weapon. The dragon is killed with a dagger, and so the dragon's existence in the story is something of a closed system. A noble sword is wielded, but in the end what woke the dragon must put it back to its rest.

Back To Top

Closing

Next week, watch for the prognostications of the messenger on Thursday! I'll also be uploading links to any British/Medieval archaelogical news that I come across.

Back To Top

Labels:

Anglo-Saxon,

Beowulf,

death,

dragon,

king,

Old English,

poetry,

swords,

translation

Thursday, October 4, 2012

Two Fallen Greats [ll.2821-2835] (Old English)

Abstract

Translation

Recordings

Showing Mourning

Seeking Meaning

Closing

Back To Top

Abstract

A reflection on Beowulf's death dwells on the dragon.

Back To Top

Translation

"That which had happened was painfully felt

by the young man, when he on the ground saw

that dearest one pitiably suffering

at his life's end. The slayer also lay so,

the terrible earth dragon was bereaved of life,

by ruin overwhelmed. In the hoard of rings no

longer could the coiled serpent be on guard,

once he by sword edge was carried off,

hard, battle-sharp remnant of hammers,so

that the wide flier by wounds was still and

fallen on earth near the treasure house. Never

after did he move about through the air by flight

in the middle of the night, in his rich possession

glorying, never could he make more appearances,

since he fell to earth at the war leader's deed of the

hand."

(Beowulf ll.2821-2835)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

Modern English:

Back To Top

Showing Mourning

The first question to surface here, like the hideous sea beasts pulled from Grendel's Mother's mire, is why a section of the poem that's showing Wiglaf's grief for Beowulf immediately after his death dwells so long on the dragon rather than Beowulf.

It could be that the poet/scribe went this way because so much of the rest of the poem is given over to Beowulf. Or it could be that Wiglaf's attention is simply drawn to the dragon because of the sheer spectacle of the sight. Though, it could also be that Wiglaf looks over to the dragon for the sake of contrast, to put off the reality of Beowulf's death for just a short time so that he, as all but Beowulf's named successor, can have a brief respite before he must coldly go forth and fulfil his duty as the new Geatish leader.

Of course, it could also be the poet's own voice that pulls away from Wiglaf at this point, leaving his perspective behind for a time to turn a little more omniscient, and to give us, the listers/readers a view of the dragon as it lay dead so that we can contrast it with Beowulf.

Back To Top

Seeking Meaning

Germanic culture widely held that dragons were symbols of the greed that would undermine the gift-centric Germanic society. So perhaps the focus on the dragon and the recounting of how it can no longer do anyone any harm suggests that greed itself has been defeated, and by one so noble as to sacrifice his own good for going against the advice of his counsel and fighting the dragon.

Maybe even the defeat of greed and the destruction of the Geats themselves that is an almost inevitable result (since they're now kingless and sitting on all of this gold) are related.

If this version of the poem is as Christian as some believe, then this shift over to the dragon shouldn't be read as Wiglaf's or the poet/scribe's attempt to contrast a death with a death, but instead as a way to show that the perfection of a society through the defeat of its greatest evil leaves that society at its end.

If Beowulf was ever used as a missionary tale, then this part of the poem could well be that which attempts to sooth potential converts into the belief that in becoming Christian their previous beliefs die off and they enter into something more perfect.

Or, again, their physical being ends, but just as Beowulf persisted up until he defeats his society's major evil, so too would the spirit of the assimilated society persist in its people. Plus, missionaries would probably say the new converts were all imbued with the spark of life that, in the Christian tradition, is generally regarded as a spoken thing - just as this story itself would've been at the time, even after having been written out.

Back To Top

Closing

So could this episode in the Beowulf saga be another key moment in the use of the poem as missionary propaganda, or is it just the poet/scribe's representation of Wiglaf's mourning? Leave a comment in the box to let me know your thoughts!

Next week, stanza three of "Dum Diane vitrea" will drop, and Wiglaf meets the cowardly thanes as they slink onto the scene.

Back To Top

Translation

Recordings

Showing Mourning

Seeking Meaning

Closing

Back To Top

Abstract

A reflection on Beowulf's death dwells on the dragon.

Back To Top

Translation

"That which had happened was painfully felt

by the young man, when he on the ground saw

that dearest one pitiably suffering

at his life's end. The slayer also lay so,

the terrible earth dragon was bereaved of life,

by ruin overwhelmed. In the hoard of rings no

longer could the coiled serpent be on guard,

once he by sword edge was carried off,

hard, battle-sharp remnant of hammers,so

that the wide flier by wounds was still and

fallen on earth near the treasure house. Never

after did he move about through the air by flight

in the middle of the night, in his rich possession

glorying, never could he make more appearances,

since he fell to earth at the war leader's deed of the

hand."

(Beowulf ll.2821-2835)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

Modern English:

Back To Top

Showing Mourning

The first question to surface here, like the hideous sea beasts pulled from Grendel's Mother's mire, is why a section of the poem that's showing Wiglaf's grief for Beowulf immediately after his death dwells so long on the dragon rather than Beowulf.

It could be that the poet/scribe went this way because so much of the rest of the poem is given over to Beowulf. Or it could be that Wiglaf's attention is simply drawn to the dragon because of the sheer spectacle of the sight. Though, it could also be that Wiglaf looks over to the dragon for the sake of contrast, to put off the reality of Beowulf's death for just a short time so that he, as all but Beowulf's named successor, can have a brief respite before he must coldly go forth and fulfil his duty as the new Geatish leader.

Of course, it could also be the poet's own voice that pulls away from Wiglaf at this point, leaving his perspective behind for a time to turn a little more omniscient, and to give us, the listers/readers a view of the dragon as it lay dead so that we can contrast it with Beowulf.

Back To Top

Seeking Meaning

Germanic culture widely held that dragons were symbols of the greed that would undermine the gift-centric Germanic society. So perhaps the focus on the dragon and the recounting of how it can no longer do anyone any harm suggests that greed itself has been defeated, and by one so noble as to sacrifice his own good for going against the advice of his counsel and fighting the dragon.

Maybe even the defeat of greed and the destruction of the Geats themselves that is an almost inevitable result (since they're now kingless and sitting on all of this gold) are related.

If this version of the poem is as Christian as some believe, then this shift over to the dragon shouldn't be read as Wiglaf's or the poet/scribe's attempt to contrast a death with a death, but instead as a way to show that the perfection of a society through the defeat of its greatest evil leaves that society at its end.

If Beowulf was ever used as a missionary tale, then this part of the poem could well be that which attempts to sooth potential converts into the belief that in becoming Christian their previous beliefs die off and they enter into something more perfect.

Or, again, their physical being ends, but just as Beowulf persisted up until he defeats his society's major evil, so too would the spirit of the assimilated society persist in its people. Plus, missionaries would probably say the new converts were all imbued with the spark of life that, in the Christian tradition, is generally regarded as a spoken thing - just as this story itself would've been at the time, even after having been written out.

Back To Top

Closing

So could this episode in the Beowulf saga be another key moment in the use of the poem as missionary propaganda, or is it just the poet/scribe's representation of Wiglaf's mourning? Leave a comment in the box to let me know your thoughts!

Next week, stanza three of "Dum Diane vitrea" will drop, and Wiglaf meets the cowardly thanes as they slink onto the scene.

Back To Top

Labels:

Anglo-Saxon,

Beowulf,

death,

dragon,

medieval,

Old English,

poetry,

translation,

Wiglaf

Thursday, September 20, 2012

Translation and the Bejewelled Truth [ll.2794-2808] (Old English)

A quick note: I realize that I had planned the first entry for the poem "Dum Diane vitrea" this past Tuesday. However, since I was quite distracted by travelling to Toronto for a Peter Gabriel concert by way of Guelph, that entry was not published. Watch for it next week, and my apologies for missing a beat. I've got my rhtyhm back now, though.

So, onwards!

Abstract

Translation

Recordings

The Facets of Translation

Answering Questions Raised

Probing Possibility

Closing

Back To Top

Abstract

Beowulf gives thanks for his seeing the dragon's treasure, and gives Wiglaf instructions for his funerary arrangements.

Back To Top

Translation

"'I for all of these precious things thank the Lord,

spoke these words the king of glory,

eternal lord, that I here look in on,

for the fact that I have been permitted to gain

such for my people before my day of death.

Now that I the treasure hoard have bought

with my old life, still attend to the

need of my people; for I may not be here longer.

Command the famed in battle to build a splendid barrow

after the pyre at the promontory over the sea;

it is to be a memorial to my people

high towering on Whale's Ness,

so that seafarers may later call it

Beowulf's Barrow, those who in ships

over the sea mists come sailing from afar.'"

(Beowulf ll.2794-2808)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

Modern English:

Back To Top

The Facets of Translation

The most prominent feature of this week's passage is the awkward opening sentence.

Its gist is straightfrward enough: Beowulf is thanking what we can safely guess is the Christian god for his successes, as he has done previously. However, if translating things fairly literally (perhaps too literally), we wind up with a second clause about the words being spoken by god ("wuldurcyninge wordum secge" ll.2795). Many translations omit this line since it appears to just repeat and expand upon Beowulf's thanks to god, as it could come out as "[I...]speak these words to the king of glory."

Yet, and this is where I exert a bit of extra pressure on the text, I've translated the second line as a reference to the jewels and the like being the words of god.

The reason for taking this route with the translation is simple: it gives the reader the opportunity to interpret the dragon's hoard as the words of god, as some sort of cosmological truth as spoken directly by the creator of those cosmos. Opening up this possibility forces readers to take another look at the dragon, too. It's still antagonistic in that it's keeping the words of god to itself and needs to be killed for them to be distributed, but then just what kind of entity is it?

It might stretching things to the breaking point, but it seems that the dragon could be interpreted as the powerful priesthood or any entrenched exclusionary religious group, and Beowulf could then be considered some kind of scholar, wrenching the truth from those who are in places of religious power and being ready to redistribute it. Though, as we find out later in the poem, this doesn't happen since the treasure is buried with Beowulf since the Geats consider it too dangerous to add massive wealth to their leader-less state.

Back To Top

Answering Questions Raised

In this reading of the hoard as cosmological truth, we need to consider what it means for Beowulf to die for it. One possibility is that in taking on such a major source of authority he destroys all of his own credibility, and as a result the truth that he uncovers can't be successfully transmitted since without credibility (or in more contemporary terms, authority or auctoritas) no one will willingly accept what he has to say.

That brings us around the matters of the theif and of Wiglaf. In this interpretation of the dragon's hoard as some sort of great truth, the theif could well be one who haplessly leaked one of its aspects and therefore set the whole of Beowulf's kingdom astir. A little bit of knowledge can be much more dangerous than a lot, after all.

As per Wiglaf, he could be an acolyte of the elder scholar Beowulf. He could be a youth who has joined his cause when noone else was brave enough to, and who cared enough for the tradition of truth than the institution which had grown up and kept it from the masses.

Back To Top

Probing Possibility

The last question that this interpretation needs to face is whether or not it could have been knowingly injected into a poem written down by people working for the medieval church, an institution that was rarely free from accusations of withholding knowledge or working contrarily to the truth of things. Representing the church as a dragon, something commonly equated with the devil, could be risky in a medieval context, but I argue that this interpretation of the dragon's hoard would hold up since the dragon could be explained as a symbol only for the corrupt within the Church and not necessarily the Church itself.

So, do you think that this interpretation holds water, or am I just stretching my own credibility by trying to keep my translation as literal as I can? Or, for that matter, have I missed something in my translation? Let me know in the comments!

Back To Top

Closing

Next week, the full complement of a Latin and Old English entry will return, with the first verse of "Dum Diane vitrea" and Beowulf's further final words to Wiglaf.

Back To Top

So, onwards!

Abstract

Translation

Recordings

The Facets of Translation

Answering Questions Raised

Probing Possibility

Closing

Back To Top

Abstract

Beowulf gives thanks for his seeing the dragon's treasure, and gives Wiglaf instructions for his funerary arrangements.

Back To Top

Translation

"'I for all of these precious things thank the Lord,

spoke these words the king of glory,

eternal lord, that I here look in on,

for the fact that I have been permitted to gain

such for my people before my day of death.

Now that I the treasure hoard have bought

with my old life, still attend to the

need of my people; for I may not be here longer.

Command the famed in battle to build a splendid barrow

after the pyre at the promontory over the sea;

it is to be a memorial to my people

high towering on Whale's Ness,

so that seafarers may later call it

Beowulf's Barrow, those who in ships

over the sea mists come sailing from afar.'"

(Beowulf ll.2794-2808)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

Modern English:

Back To Top

The Facets of Translation

The most prominent feature of this week's passage is the awkward opening sentence.

Its gist is straightfrward enough: Beowulf is thanking what we can safely guess is the Christian god for his successes, as he has done previously. However, if translating things fairly literally (perhaps too literally), we wind up with a second clause about the words being spoken by god ("wuldurcyninge wordum secge" ll.2795). Many translations omit this line since it appears to just repeat and expand upon Beowulf's thanks to god, as it could come out as "[I...]speak these words to the king of glory."

Yet, and this is where I exert a bit of extra pressure on the text, I've translated the second line as a reference to the jewels and the like being the words of god.

The reason for taking this route with the translation is simple: it gives the reader the opportunity to interpret the dragon's hoard as the words of god, as some sort of cosmological truth as spoken directly by the creator of those cosmos. Opening up this possibility forces readers to take another look at the dragon, too. It's still antagonistic in that it's keeping the words of god to itself and needs to be killed for them to be distributed, but then just what kind of entity is it?

It might stretching things to the breaking point, but it seems that the dragon could be interpreted as the powerful priesthood or any entrenched exclusionary religious group, and Beowulf could then be considered some kind of scholar, wrenching the truth from those who are in places of religious power and being ready to redistribute it. Though, as we find out later in the poem, this doesn't happen since the treasure is buried with Beowulf since the Geats consider it too dangerous to add massive wealth to their leader-less state.

Back To Top

Answering Questions Raised

In this reading of the hoard as cosmological truth, we need to consider what it means for Beowulf to die for it. One possibility is that in taking on such a major source of authority he destroys all of his own credibility, and as a result the truth that he uncovers can't be successfully transmitted since without credibility (or in more contemporary terms, authority or auctoritas) no one will willingly accept what he has to say.

That brings us around the matters of the theif and of Wiglaf. In this interpretation of the dragon's hoard as some sort of great truth, the theif could well be one who haplessly leaked one of its aspects and therefore set the whole of Beowulf's kingdom astir. A little bit of knowledge can be much more dangerous than a lot, after all.

As per Wiglaf, he could be an acolyte of the elder scholar Beowulf. He could be a youth who has joined his cause when noone else was brave enough to, and who cared enough for the tradition of truth than the institution which had grown up and kept it from the masses.

Back To Top

Probing Possibility

The last question that this interpretation needs to face is whether or not it could have been knowingly injected into a poem written down by people working for the medieval church, an institution that was rarely free from accusations of withholding knowledge or working contrarily to the truth of things. Representing the church as a dragon, something commonly equated with the devil, could be risky in a medieval context, but I argue that this interpretation of the dragon's hoard would hold up since the dragon could be explained as a symbol only for the corrupt within the Church and not necessarily the Church itself.

So, do you think that this interpretation holds water, or am I just stretching my own credibility by trying to keep my translation as literal as I can? Or, for that matter, have I missed something in my translation? Let me know in the comments!

Back To Top

Closing

Next week, the full complement of a Latin and Old English entry will return, with the first verse of "Dum Diane vitrea" and Beowulf's further final words to Wiglaf.

Back To Top

Thursday, August 16, 2012

The Emptiness of All that Gold [ll.2771b-82] (Old English)

Abstract

Translation

Recordings

The Hoard's Sheer Immensity

The Golden Power

Closing

Back To Top

Abstract

The dragon is dwelled on, while Wiglaf wanders through the hoard.

Back To Top

Translation

"None of that sight there

was for the serpent, when the blade carried him off.

Then, I have heard, the hoard in the barrow, ancient

work of giants, was ransacked by one man, he loaded

his lap with drinking vessels and dishes of his own

choosing, the standard he also took, brightest of banners.

The sword earlier had injured - the blade was iron - that

of the aged lord, that was the treasure's guardian for

a long time, terrifying fire brought

hot from the hoard, fiercely willing in

the middle of the night, until he a violent death died."

(Beowulf ll.2771b-82)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

{Forthcoming}

Modern English:

{Forthcoming}

Back To Top

The Hoard's Sheer Immensity

Already it's been mentioned how Wiglaf is not referred to by name for some time after this point, but here the poet/scribe takes this lack of identity to a strange place.

Instead of referring to Wiglaf via synecdoche with a piece of a warrior's equipment, or calling him a "thane" or "fighter," the poet/scribe simply calls Wiglaf "one man" ("ānne mannan" (l.2774)).

The effect of this pronoun and its adjective is immense.

However, this immensity doesn't come from the alienation that the poet/scribe subjects Wiglaf to, but rather from the sheer size of the hoard that the poet/scribe's making Wiglaf suddenly so small implies. Don't forget that because of that shining banner everything is now illuminated, so we can liken this part of the poem to a long panning shot that might be used in movies to show a suddenly-broken-into, vast treasure chamber in an ancient temple or tomb.

Yet, it's curious that the poet/scribe describes the immensity of the hoard in this way, especially since there's so much build up to it.

We hear about it when the thief stumbles into it (ll.2283-4), again when Beowulf and his thanes head to the barrow (ll.2412-3), and then again in Beowulf's command to Wiglaf (ll.2745-6).

Plus, any Anglo-Saxon would have been practically salivating at the prospect of finding so much treasure all in one spot - becoming instantly wealthy and instantaneously being able to exercise huge influence over others through gifts, thereby shoring up his or her own reputation and social network so that they would be more secure than gold alone would allow.

Back To Top

The Golden Power

In fact, it's exactly within the gold-giving culture of the Anglo Saxons that we can find another reason for the poet/scribe's describing the hoard as he does.

Rather than focus on how much there is, the poet/scribe has described the hoard through a kind of lack. It's big and immense, but it's the sort of thing that you can lose yourself in - even if you're a loyal thane who's already pledged your very being to help your lord in his dying moments.

And this is what makes the dragon's hoard so dreadful. It's big, it's vast, it's unwieldy.

No one could use that much gold for social reasons, and the temptation to fall into self-indulgence (as Heremod does in the story Hrothgar tells Beowulf (ll.1709-1722)) is practically irresistible. If there is a curse on the gold, that is the curse: to be instantly given so much that you don't know what to do with yourself so you revert to an animalistic state.

Some have even theorized that the survivor who sings the "Lay of the Last Survivor" (ll.2247–66) somehow became the dragon: The last of his kind pining away over the treasure that could not buy back the lives of his fallen people or return them to their former glory.

This might also explain why the dragon is so prominently featured in this passage, despite his being long since dead. As Beowulf's wishes have taken over Wiglaf's identity, now the dragon's identity, the miserly lord of plenty, threatens to do the same. Yet ultimately Wiglaf resists, for the poet/scribe sings that the dragon "a violent death died" ("hē morðre swealt" (l.2782)) to round out Wiglaf's time in the hoard.

Back To Top

Closing

Next week, this blog will be on break. I've fallen too far behind in the recordings to keep heading onwards and since I finished "O Fortuna" this week, I want to give myself time to catch up before moving onto my next Latin text.

In the meantime be sure to check my past entries and recordings, and if you like what you read and hear, feel free to support my efforts here!

Back To Top

Translation

Recordings

The Hoard's Sheer Immensity

The Golden Power

Closing

Back To Top

Abstract

The dragon is dwelled on, while Wiglaf wanders through the hoard.

Back To Top

Translation

"None of that sight there

was for the serpent, when the blade carried him off.

Then, I have heard, the hoard in the barrow, ancient

work of giants, was ransacked by one man, he loaded

his lap with drinking vessels and dishes of his own

choosing, the standard he also took, brightest of banners.

The sword earlier had injured - the blade was iron - that

of the aged lord, that was the treasure's guardian for

a long time, terrifying fire brought

hot from the hoard, fiercely willing in

the middle of the night, until he a violent death died."

(Beowulf ll.2771b-82)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

{Forthcoming}

Modern English:

{Forthcoming}

Back To Top

The Hoard's Sheer Immensity

Already it's been mentioned how Wiglaf is not referred to by name for some time after this point, but here the poet/scribe takes this lack of identity to a strange place.

Instead of referring to Wiglaf via synecdoche with a piece of a warrior's equipment, or calling him a "thane" or "fighter," the poet/scribe simply calls Wiglaf "one man" ("ānne mannan" (l.2774)).

The effect of this pronoun and its adjective is immense.

However, this immensity doesn't come from the alienation that the poet/scribe subjects Wiglaf to, but rather from the sheer size of the hoard that the poet/scribe's making Wiglaf suddenly so small implies. Don't forget that because of that shining banner everything is now illuminated, so we can liken this part of the poem to a long panning shot that might be used in movies to show a suddenly-broken-into, vast treasure chamber in an ancient temple or tomb.

Yet, it's curious that the poet/scribe describes the immensity of the hoard in this way, especially since there's so much build up to it.

We hear about it when the thief stumbles into it (ll.2283-4), again when Beowulf and his thanes head to the barrow (ll.2412-3), and then again in Beowulf's command to Wiglaf (ll.2745-6).

Plus, any Anglo-Saxon would have been practically salivating at the prospect of finding so much treasure all in one spot - becoming instantly wealthy and instantaneously being able to exercise huge influence over others through gifts, thereby shoring up his or her own reputation and social network so that they would be more secure than gold alone would allow.

Back To Top

The Golden Power

In fact, it's exactly within the gold-giving culture of the Anglo Saxons that we can find another reason for the poet/scribe's describing the hoard as he does.

Rather than focus on how much there is, the poet/scribe has described the hoard through a kind of lack. It's big and immense, but it's the sort of thing that you can lose yourself in - even if you're a loyal thane who's already pledged your very being to help your lord in his dying moments.

And this is what makes the dragon's hoard so dreadful. It's big, it's vast, it's unwieldy.

No one could use that much gold for social reasons, and the temptation to fall into self-indulgence (as Heremod does in the story Hrothgar tells Beowulf (ll.1709-1722)) is practically irresistible. If there is a curse on the gold, that is the curse: to be instantly given so much that you don't know what to do with yourself so you revert to an animalistic state.

Some have even theorized that the survivor who sings the "Lay of the Last Survivor" (ll.2247–66) somehow became the dragon: The last of his kind pining away over the treasure that could not buy back the lives of his fallen people or return them to their former glory.

This might also explain why the dragon is so prominently featured in this passage, despite his being long since dead. As Beowulf's wishes have taken over Wiglaf's identity, now the dragon's identity, the miserly lord of plenty, threatens to do the same. Yet ultimately Wiglaf resists, for the poet/scribe sings that the dragon "a violent death died" ("hē morðre swealt" (l.2782)) to round out Wiglaf's time in the hoard.

Back To Top

Closing

Next week, this blog will be on break. I've fallen too far behind in the recordings to keep heading onwards and since I finished "O Fortuna" this week, I want to give myself time to catch up before moving onto my next Latin text.

In the meantime be sure to check my past entries and recordings, and if you like what you read and hear, feel free to support my efforts here!

Back To Top

Thursday, August 2, 2012

On Requests and Namelessness [ll.2743b-2755] (Old English)

Abstract

Translation

Recordings

Digging Deeper into Beowulf's Request

Going Nameless

Closing

Back To Top

Abstract

Beowulf instructs Wiglaf to get some gold from the hoard to show him what he fought for, and Wiglaf runs off to oblige him.

Back To Top

Translation

"Now go you quickly

to see the hoard under the grey stone,

dear Wiglaf, now the serpent lay dead,

sleeping in death sorely wounded, deprived of treasure.

Be now in haste that I ancient riches,

the store of gold may see, clearly look at

the bright finely worked jewels, so that I may the more

peacefully after the wealth of treasure leave my

life and lordship; that which I have long held.'

I have heard that then the son of Weohstan quickly obeyed

after the spoken word of his lord in wounds and

in war weariness, bearing mailcoat

the broad ring-shirt, under the barrow’s roof."

(Beowulf ll.2743b-2755)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

{Forthcoming}

Modern English:

{Forthcoming}

Back To Top

Digging Deeper into Beowulf's Request

On the surface, Beowulf's request seems simple enough. 'Go and grab some gold, that I may be able to see it,' but there's more to it then a validation of his final battle. Within this request lay the very stuff of revenge.

Beowulf acknowledges that now the serpent is dead and thus "deprived of treasure" ("since bereafod" (l.2746)). Thus, were he to die without seeing what he had fought for then, he would, in a way, not have won at all.

For Beowulf would then not have been able to say that he had laid eyes on that for which he fought, while the dragon enjoyed the sight of it constantly. Further, he also wouldn't have experienced it, and wouldn't therefore have fulifilled the treasure's basic purpose: to be used by being enjoyed through sight (just as a grammatical object is used simply by being linked to a grammatical subject).

However, the act of seeing it, of using it, also puts Beowulf on par with the dragon on the level of greed, since he is not able to dole out the treasure to his people, as any good king must, in person.

Back To Top

Going Nameless

But, what's curious about this passage is Wiglaf's lacking reference by name. First he is the "son of Weohstan" and then he is referred to with a bit of metonymy when the poet simply says that he bore a mailcoat into the barrow ("hringnet beran/...under beorges hrof" (ll.2754-2755)).

So why does Wiglaf, the one who was instrumental in Beowulf's victory, suddenly lose his name? Perhaps to keep the focus on Beowulf, rather than Wiglaf so that it truly does become an elegy rather than a story of succession, of hope.

It's also possible that this is merely poetic license, but the fact is that Wiglaf is not referred to by name again until line 2852. That's over one hundred lines later, and the point at which his fellow Geats recognize him as the new leader for the first time.

That Wiglaf is named for the occasion of recognition as the new authority strongly suggests that indeed he is occluded for the next 100 lines to keep Beowulf in the spotlight. Going out at Beowulf's behest, Wiglaf isn't really Wiglaf anymore, but he is made into Beowulf's double, at least for the brief time that he scrambles out to the hoard, through it, and back.

It could even be argued, that Wiglaf's washing Beowulf clean and then undoing his helmet are both acts that signify a complete rescindment of the will, perhaps as an acknowledgement of the end of a life. In doing these things Wiglaf drops his own desires and takes up Beowulf's request entirely so that he can be a comfort to the old lord in his final moments.

Back To Top

Closing

Next week, the second stanza of "O Fortuna" will be posted, and Wiglaf, though nameless, finds himself immersed in a fabulous treasure room.

Back To Top

Translation

Recordings

Digging Deeper into Beowulf's Request

Going Nameless

Closing

Back To Top

Abstract

Beowulf instructs Wiglaf to get some gold from the hoard to show him what he fought for, and Wiglaf runs off to oblige him.

Back To Top

Translation

"Now go you quickly

to see the hoard under the grey stone,

dear Wiglaf, now the serpent lay dead,

sleeping in death sorely wounded, deprived of treasure.

Be now in haste that I ancient riches,

the store of gold may see, clearly look at

the bright finely worked jewels, so that I may the more

peacefully after the wealth of treasure leave my

life and lordship; that which I have long held.'

I have heard that then the son of Weohstan quickly obeyed

after the spoken word of his lord in wounds and

in war weariness, bearing mailcoat

the broad ring-shirt, under the barrow’s roof."

(Beowulf ll.2743b-2755)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

{Forthcoming}

Modern English:

{Forthcoming}

Back To Top

Digging Deeper into Beowulf's Request

On the surface, Beowulf's request seems simple enough. 'Go and grab some gold, that I may be able to see it,' but there's more to it then a validation of his final battle. Within this request lay the very stuff of revenge.

Beowulf acknowledges that now the serpent is dead and thus "deprived of treasure" ("since bereafod" (l.2746)). Thus, were he to die without seeing what he had fought for then, he would, in a way, not have won at all.

For Beowulf would then not have been able to say that he had laid eyes on that for which he fought, while the dragon enjoyed the sight of it constantly. Further, he also wouldn't have experienced it, and wouldn't therefore have fulifilled the treasure's basic purpose: to be used by being enjoyed through sight (just as a grammatical object is used simply by being linked to a grammatical subject).

However, the act of seeing it, of using it, also puts Beowulf on par with the dragon on the level of greed, since he is not able to dole out the treasure to his people, as any good king must, in person.

Back To Top

Going Nameless

But, what's curious about this passage is Wiglaf's lacking reference by name. First he is the "son of Weohstan" and then he is referred to with a bit of metonymy when the poet simply says that he bore a mailcoat into the barrow ("hringnet beran/...under beorges hrof" (ll.2754-2755)).

So why does Wiglaf, the one who was instrumental in Beowulf's victory, suddenly lose his name? Perhaps to keep the focus on Beowulf, rather than Wiglaf so that it truly does become an elegy rather than a story of succession, of hope.

It's also possible that this is merely poetic license, but the fact is that Wiglaf is not referred to by name again until line 2852. That's over one hundred lines later, and the point at which his fellow Geats recognize him as the new leader for the first time.

That Wiglaf is named for the occasion of recognition as the new authority strongly suggests that indeed he is occluded for the next 100 lines to keep Beowulf in the spotlight. Going out at Beowulf's behest, Wiglaf isn't really Wiglaf anymore, but he is made into Beowulf's double, at least for the brief time that he scrambles out to the hoard, through it, and back.

It could even be argued, that Wiglaf's washing Beowulf clean and then undoing his helmet are both acts that signify a complete rescindment of the will, perhaps as an acknowledgement of the end of a life. In doing these things Wiglaf drops his own desires and takes up Beowulf's request entirely so that he can be a comfort to the old lord in his final moments.

Back To Top

Closing

Next week, the second stanza of "O Fortuna" will be posted, and Wiglaf, though nameless, finds himself immersed in a fabulous treasure room.

Back To Top

Thursday, June 28, 2012

A Co-ordinated Dragon Kill [ll.2688-2705] (Old English)

Abstract

Translation

Recordings

When Words Flash, Sharp as Swords

A Matter of Succession

Closing

Back To Top

Abstract

Thanks to a team effort, Beowulf and Wiglaf bring down the dragon.

Back To Top

Translation

"Then the ravager of a people for a third time,

the terrible fire dragon intent on a hostile deed,

rushed on that renowned one when for him the opportunity

permitted, hot and battle fierce. All of his neck was

clasped by sharp tusks; he was made to become bloody

with ichor, gore in waves surged out.

Then, as I have heard, the soldier by his side showed

known courage for his liege lord,

strength and boldness, as was inborn.

He worked not upon the head, but the hand of that daring

man was burned, when he his kin helped by striking

a little lower at the strife-stranger with blade full

of cunning, so that the decorated sword, gleaming and

gold-adorned, stuck in the beast's stomach so that the

fire began to abate afterwards. Then once more the king

himself wielded his wit, brandished a hip-blade, bitter

and battle-sharp, that he wore on his byrnie;

the protector of the Weders cleaved the dragon in its

middle."

(Beowulf ll.2688-2705)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

{Forthcoming}

Modern English:

{Forthcoming}

Back To Top

When Words Flash, Sharp as Swords

The words here are definitely meant to mimic the flashing of blades. The exact words are different, of course, being translated, but the description of the duo's weapons and their working is preserved.

The descriptive phrases "sword full of cunning, so that the decorated sword,/gleaming and gold-adorned" ("þæt ðæt sweord gedēaf,/

fāh ond fǣted" (ll.2700-2701)) and "brandished a hip-blade,/bitter and battle-sharp," ("wællseaxe gebrǣd/biter ond beaduscearp" (ll.2703-2704)) in both Englishes still give a vivid image of steel being swung or stabbing, all the while glittering with either jewels or fatal intent.

Such description and rhetorical use of language is effective here because it brings listeners/readers into the action of the poem while also reminding them of the extreme danger of the dragon. After all, the gleam of Wiglaf's sword is likely as much due to whatever natural light is available as it is to the dragon's fire illuminating it; and Beowulf's "bitter and battle-sharp" dagger, drawn with wit, reminds us of the kind of cunning required to slay something so ancient, deadly, and tricky in its own right.

Back To Top

A Matter of Succession

If there was ever a history of Wiglaf penned by a monk or sung by a bard, and if that history involved a successor, it would not be surprising if Wiglaf's successor helped him win his final battle.

Kingship is something that needs to be continuous, lest a contest for the throne result in the destruction of a house, much like the case of Haethcyn and Herebeald. And there is no better way to pass on kingship than to slay a dragon with your successor.

In fact, if the line of kings is regarded as a kind of chain, Wiglaf's selfless stabbing of the dragon below its armored head is exactly where his link connects to that of Beowulf as the poem's hero rallies and defeats the dragon, drawing his own link on the chain of kingship (and, *spoilers* his life */spoilers*) to a close.

But Neil Gaiman wasn't far from the mark when he has Wiglaf succeed Beowulf, for although it may be short lived, Wiglaf's succession of Beowulf is exactly what this team effort solidifies.

Back To Top

Closing

Next week, this blog will be on break so that what's here can be tidied up, recordings can be posted, and a new page can be launched. But, in the meantime, I'll be updating my other blog every day of the week, so check it out at http://glarkly.blogspot.ca!

Back To Top

Translation

Recordings

When Words Flash, Sharp as Swords

A Matter of Succession

Closing

Back To Top

Abstract

Thanks to a team effort, Beowulf and Wiglaf bring down the dragon.

Back To Top

Translation

"Then the ravager of a people for a third time,

the terrible fire dragon intent on a hostile deed,

rushed on that renowned one when for him the opportunity

permitted, hot and battle fierce. All of his neck was

clasped by sharp tusks; he was made to become bloody

with ichor, gore in waves surged out.

Then, as I have heard, the soldier by his side showed

known courage for his liege lord,

strength and boldness, as was inborn.

He worked not upon the head, but the hand of that daring

man was burned, when he his kin helped by striking

a little lower at the strife-stranger with blade full

of cunning, so that the decorated sword, gleaming and

gold-adorned, stuck in the beast's stomach so that the

fire began to abate afterwards. Then once more the king

himself wielded his wit, brandished a hip-blade, bitter

and battle-sharp, that he wore on his byrnie;

the protector of the Weders cleaved the dragon in its

middle."

(Beowulf ll.2688-2705)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

{Forthcoming}

Modern English:

{Forthcoming}

Back To Top

When Words Flash, Sharp as Swords

The words here are definitely meant to mimic the flashing of blades. The exact words are different, of course, being translated, but the description of the duo's weapons and their working is preserved.

The descriptive phrases "sword full of cunning, so that the decorated sword,/gleaming and gold-adorned" ("þæt ðæt sweord gedēaf,/

fāh ond fǣted" (ll.2700-2701)) and "brandished a hip-blade,/bitter and battle-sharp," ("wællseaxe gebrǣd/biter ond beaduscearp" (ll.2703-2704)) in both Englishes still give a vivid image of steel being swung or stabbing, all the while glittering with either jewels or fatal intent.

Such description and rhetorical use of language is effective here because it brings listeners/readers into the action of the poem while also reminding them of the extreme danger of the dragon. After all, the gleam of Wiglaf's sword is likely as much due to whatever natural light is available as it is to the dragon's fire illuminating it; and Beowulf's "bitter and battle-sharp" dagger, drawn with wit, reminds us of the kind of cunning required to slay something so ancient, deadly, and tricky in its own right.

Back To Top

A Matter of Succession

If there was ever a history of Wiglaf penned by a monk or sung by a bard, and if that history involved a successor, it would not be surprising if Wiglaf's successor helped him win his final battle.

Kingship is something that needs to be continuous, lest a contest for the throne result in the destruction of a house, much like the case of Haethcyn and Herebeald. And there is no better way to pass on kingship than to slay a dragon with your successor.

In fact, if the line of kings is regarded as a kind of chain, Wiglaf's selfless stabbing of the dragon below its armored head is exactly where his link connects to that of Beowulf as the poem's hero rallies and defeats the dragon, drawing his own link on the chain of kingship (and, *spoilers* his life */spoilers*) to a close.

But Neil Gaiman wasn't far from the mark when he has Wiglaf succeed Beowulf, for although it may be short lived, Wiglaf's succession of Beowulf is exactly what this team effort solidifies.

Back To Top

Closing

Next week, this blog will be on break so that what's here can be tidied up, recordings can be posted, and a new page can be launched. But, in the meantime, I'll be updating my other blog every day of the week, so check it out at http://glarkly.blogspot.ca!

Back To Top

Thursday, June 21, 2012

Beowulf Strikes the Dragon's Head, and the Poet/Scribe Strikes at the Poem's Heart [ll.2672b-2687] (Old English)

Abstract

Translation

Recordings

Beowulf's Flaw, and an Old Dichotomy

Striking at the Heart of the Poem

Closing

Back To Top

Abstract

Wiglaf’s valor inspires Beowulf, but this leads to the revelation of the truth about Beowulf and his swords.

Back To Top

Translation

"Flame in a wave advanced,

burned the shield up to the boss; mail coat could not

for the young spear-warrior provide help,

but the man of youth under his kinsman’s shield

valiantly went on, when his own was

by flame destroyed. Then the war king again set

his mind on glory, struck with great strength

with the war sword, so that it in the dragon’s head stuck

and impelled hostility; Naegling broke,

failed at battle the sword of Beowulf, ancient

and grey-coloured. To him it was not granted by

fate that his sword’s edge may be a help at battle;

it was in his too strong hand, he who did so with

every sword, as I have heard, the stroke overtaxed

it, when he to battle bore any weapon wondrously

hard; it was not for him at all the better."

(Beowulf ll.2672b-2687)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

Modern English:

Back To Top

Beowulf's Flaw, and an Old Dichotomy

All heroes need a flaw.

Eddard Stark in the Song of Ice and Fire was simply too noble, Link in the Legend of Zelda games is always inexperienced, and Beowulf can’t effectively wield swords. Beowulf's particular weakness is especially interesting in relation to the rest of the poem.

On the one hand, it’s potentially a great reflection of Beowulf’s name, whether it means “bear” (bee-wolf), or is simply “wolf.” His being unable to use swords effectively (almost pervasively a symbol of cultivated, human nobility) plays well to his animalistic aspect.

Rather than fighting like a civilized man with sword and shield, Beowulf instead fights bare handed, and is indeed the better for it. After all, defeating Grendel empty-handed is a much more boast-worthy feat than defeating him with a sword, not necessarily because of the strength that it requires, but because it plays so well into the mythology around Grendel as a monster who resists iron weapons.

However, it also implies that Beowulf is somehow on a level with Grendel, who, as it is noted, "scorns/in his reckless way to use weapons" ("þæt se ǣglǣca/for his won-hȳdum wǣpna ne recceð"(ll.433-434)).

In this way, Beowulf’s prowess in unarmed combat speaks to something uncivilized in him that he's note entirely capable of controlling. After his fight with Grendel, he doesn't seem to take up sword and shield to the same effect again (after Grendel we hear no more of "sea-brutes" ("niceras" (l.422)) or trolls ("eotena" (l.421))). Except of course, in his final, fatal battle with the dragon.

Back To Top

Striking at the Heart of the Poem

The fact that the whole poem is essentially an elegy to Beowulf and the Geatish (probably, by proxy, Anglo-Saxon) culture that he is so much a part of, while also presenting Beowulf as uncivilized in war (something uncivilized in itself) might just be the strongest argument for Beowulf’s really being about the Anglo-Saxons transitioning from their own traditions to something more Christian. The brutality of empty-handed combat gives way to something regarded as more civil.

The way of the sword (very obviously a cross, if the blade is stuck into the ground), is left in the absence of the way of the brutal fist. But even the way of the sword fades, if you look beyond the far end of the poem, as the Geats are prophesied to soon meet their end as a nation (ll.3010-3030).

So in addition to elegy, the poem is also apocalyptic, indicating the end of warfare, the way of the sword, for one of the many groups in early medieval Europe. Perhaps, from a Christian perspective, this is meant to point towards a Utopian future, or Second Coming, that is inevitable if the old ways are left behind and new ones are adapted.

Back To Top

Closing

Check back next week for more of Isidore’s colorful explanations, and for the climax of the battle between team Beowulf and the dragon.

Back To Top

Translation

Recordings

Beowulf's Flaw, and an Old Dichotomy

Striking at the Heart of the Poem

Closing

|

Back To Top

Abstract

Wiglaf’s valor inspires Beowulf, but this leads to the revelation of the truth about Beowulf and his swords.

Back To Top

Translation

"Flame in a wave advanced,

burned the shield up to the boss; mail coat could not

for the young spear-warrior provide help,

but the man of youth under his kinsman’s shield

valiantly went on, when his own was

by flame destroyed. Then the war king again set

his mind on glory, struck with great strength

with the war sword, so that it in the dragon’s head stuck

and impelled hostility; Naegling broke,

failed at battle the sword of Beowulf, ancient

and grey-coloured. To him it was not granted by

fate that his sword’s edge may be a help at battle;

it was in his too strong hand, he who did so with

every sword, as I have heard, the stroke overtaxed

it, when he to battle bore any weapon wondrously

hard; it was not for him at all the better."

(Beowulf ll.2672b-2687)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

Modern English:

Back To Top

Beowulf's Flaw, and an Old Dichotomy

All heroes need a flaw.

Eddard Stark in the Song of Ice and Fire was simply too noble, Link in the Legend of Zelda games is always inexperienced, and Beowulf can’t effectively wield swords. Beowulf's particular weakness is especially interesting in relation to the rest of the poem.

On the one hand, it’s potentially a great reflection of Beowulf’s name, whether it means “bear” (bee-wolf), or is simply “wolf.” His being unable to use swords effectively (almost pervasively a symbol of cultivated, human nobility) plays well to his animalistic aspect.

Rather than fighting like a civilized man with sword and shield, Beowulf instead fights bare handed, and is indeed the better for it. After all, defeating Grendel empty-handed is a much more boast-worthy feat than defeating him with a sword, not necessarily because of the strength that it requires, but because it plays so well into the mythology around Grendel as a monster who resists iron weapons.

However, it also implies that Beowulf is somehow on a level with Grendel, who, as it is noted, "scorns/in his reckless way to use weapons" ("þæt se ǣglǣca/for his won-hȳdum wǣpna ne recceð"(ll.433-434)).

In this way, Beowulf’s prowess in unarmed combat speaks to something uncivilized in him that he's note entirely capable of controlling. After his fight with Grendel, he doesn't seem to take up sword and shield to the same effect again (after Grendel we hear no more of "sea-brutes" ("niceras" (l.422)) or trolls ("eotena" (l.421))). Except of course, in his final, fatal battle with the dragon.

Back To Top

Striking at the Heart of the Poem

The fact that the whole poem is essentially an elegy to Beowulf and the Geatish (probably, by proxy, Anglo-Saxon) culture that he is so much a part of, while also presenting Beowulf as uncivilized in war (something uncivilized in itself) might just be the strongest argument for Beowulf’s really being about the Anglo-Saxons transitioning from their own traditions to something more Christian. The brutality of empty-handed combat gives way to something regarded as more civil.

The way of the sword (very obviously a cross, if the blade is stuck into the ground), is left in the absence of the way of the brutal fist. But even the way of the sword fades, if you look beyond the far end of the poem, as the Geats are prophesied to soon meet their end as a nation (ll.3010-3030).

So in addition to elegy, the poem is also apocalyptic, indicating the end of warfare, the way of the sword, for one of the many groups in early medieval Europe. Perhaps, from a Christian perspective, this is meant to point towards a Utopian future, or Second Coming, that is inevitable if the old ways are left behind and new ones are adapted.

Back To Top

Closing

Check back next week for more of Isidore’s colorful explanations, and for the climax of the battle between team Beowulf and the dragon.

Back To Top

Thursday, June 14, 2012

A Chatty Wiglaf and an Encouraged Beowulf [ll.2661-2672a] (Old English)

Abstract

Translation

Recordings

Wiglaf: The Chatty Youth

An Early Ascension Speech?

Closing

Back To Top

Abstract

Wiglaf rushes over to Beowulf, and reassures him that his glory will not falter for this difficulty. But, just as Wiglaf finishes his short speech, the dragon starts back towards the pair.

Back To Top

Translation

"Advanced he then through that deadly smoke, in helmet

he bore to the lord his help, few words he spoke:

'Dear Beowulf, perform all well,

just as you in youth long ago said

that you would not allow while you are alive

your glory to decline; You shall now in deed be famous,

resolute prince, all strength

your life to defend; I you shall help.'

After that word the serpent angry came,

the terrible malicious alien from another time

glowing in surging fire attacked his enemy,

hateful of men."

(Beowulf ll.2661-2672a)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

Modern English:

Back To Top

Wiglaf: The Chatty Youth

Wiglaf is a very strange character. It’s not that his name is odd (aside from what’s been said before, what could naming someone “war heirloom” mean, anyway?), or that his introduction is hastily foisted onto an explanation of his equipment, but that he gets so many lines of dialog.

After all, considering the length of this poem, there really isn’t that much dialog.

Hrothgar and Beowulf have some long speeches, but they’re both in the poem for a substantial amount of time, while Wiglaf is only prominently featured in the last 500 lines or so.

So, why does Wiglaf have such a major speaking role relative to the length of his presence in the poem?

It could be that speech is shorthand for the kind of thing that his generation of Geats excels in. That the rest of his fellow thanes ran away when Beowulf’s distress became clear is a clear mark of this. Or it could be that Wiglaf, as someone who hasn’t yet seen real battle and killed with his own sword, primarily interacts with the world through speech rather than weaponry.

But then, one thing still stands out.

In almost every instance of Beowulf, the poem’s other major hero, talking, he does it in response to other characters' actions. He answers Unferth’s challenge to his valor (ll.529-606), he boasts to Wealhtheow when she presents him with a drinking cup (ll.628-638), and he retells his exploits in Daneland when Hygelac asks for a tale of his adventures (ll.1900-2162).

Otherwise, Beowulf is mostly a silent protagonist. The only major instance where he speaks unbidden is before his thanes, when he gives them his lengthy autobiography and assures them that this dragon fight will be tough, but he’ll handle it himself.

Back To Top

An Early Ascension Speech?

With that in mind, is it possible that the poet/scribe behind the poem is setting Wiglaf up as the next Geatish king?

Since Beowulf’s speech to his thanes is the product of his office as well as his emotional state at the time, the only thing that marks Wiglaf as different is his lack of a title. Perhaps his outburst is meant to stand as a kind of shorthand for youthful vigor, a vigor that he tries to impart to or revive in Beowulf through his words of encouragement - themselves completely unbidden.

Going back to the idea that Wiglaf’s speeches are the result of his inexperience in the field of war (a man's proving grounds in the poem), maybe he is an early case study in the idea behind the phrase “fake it before you make it.”

Having no past battle experience, Wiglaf can only put on a brave face, something expressed through words, but he can’t put on a brave show aside from his apparently impulsive rush from the band of thanes to his lord’s side.

Of course, if all of this is true, then the depiction of Wiglaf speaking to his fellow thanes and rushing to his lord's side is a great portrayal of a young thane bound for great things.

Back To Top

Closing

Next week, Isidore runs through three of the colors from this week’s guide to good horses. And, in Beowulf, another hardship befalls the rallied lord of the Geats.

Back To Top

Translation

Recordings

Wiglaf: The Chatty Youth

An Early Ascension Speech?

Closing

|

Back To Top

Abstract

Wiglaf rushes over to Beowulf, and reassures him that his glory will not falter for this difficulty. But, just as Wiglaf finishes his short speech, the dragon starts back towards the pair.

Back To Top

Translation

"Advanced he then through that deadly smoke, in helmet

he bore to the lord his help, few words he spoke:

'Dear Beowulf, perform all well,

just as you in youth long ago said

that you would not allow while you are alive

your glory to decline; You shall now in deed be famous,

resolute prince, all strength

your life to defend; I you shall help.'

After that word the serpent angry came,

the terrible malicious alien from another time

glowing in surging fire attacked his enemy,

hateful of men."

(Beowulf ll.2661-2672a)

Back To Top

Recordings

Old English:

Modern English:

Back To Top

Wiglaf: The Chatty Youth